THIS IS COPPER

Copper is ubiquitous to our modern world, yet it is largely invisible. It is the first metal used by humankind, and it is crucial for a renewable future: a wind turbine alone can contain up to five tonnes of copper, and ten tonnes of the metal are needed per kilometre of high-speed railway.

But what exactly is copper? The metal we know is only part of a much wider material story. Mining overburden, tailings, metal concentrates, rare metals like gold and silver, sulfuric acid, sulphate solution, slag, and more. Our primary focus in this investigation is slag, a byproduct of producing copper. Slag is the molten impurities cast aside during the smelting process into large mountainous heaps.

Slag is an inevitability of most metal production. The by-product is produced both during extraction directly from ore as well as recycling of scrap metal. Slag is also the reminder of an imperfect process, a residue left behind as a manmade stone. Remains of slag exist from ancient times speaking of long lost civilizations, and will remain far into the future to speak of our own.

![]()

![]()

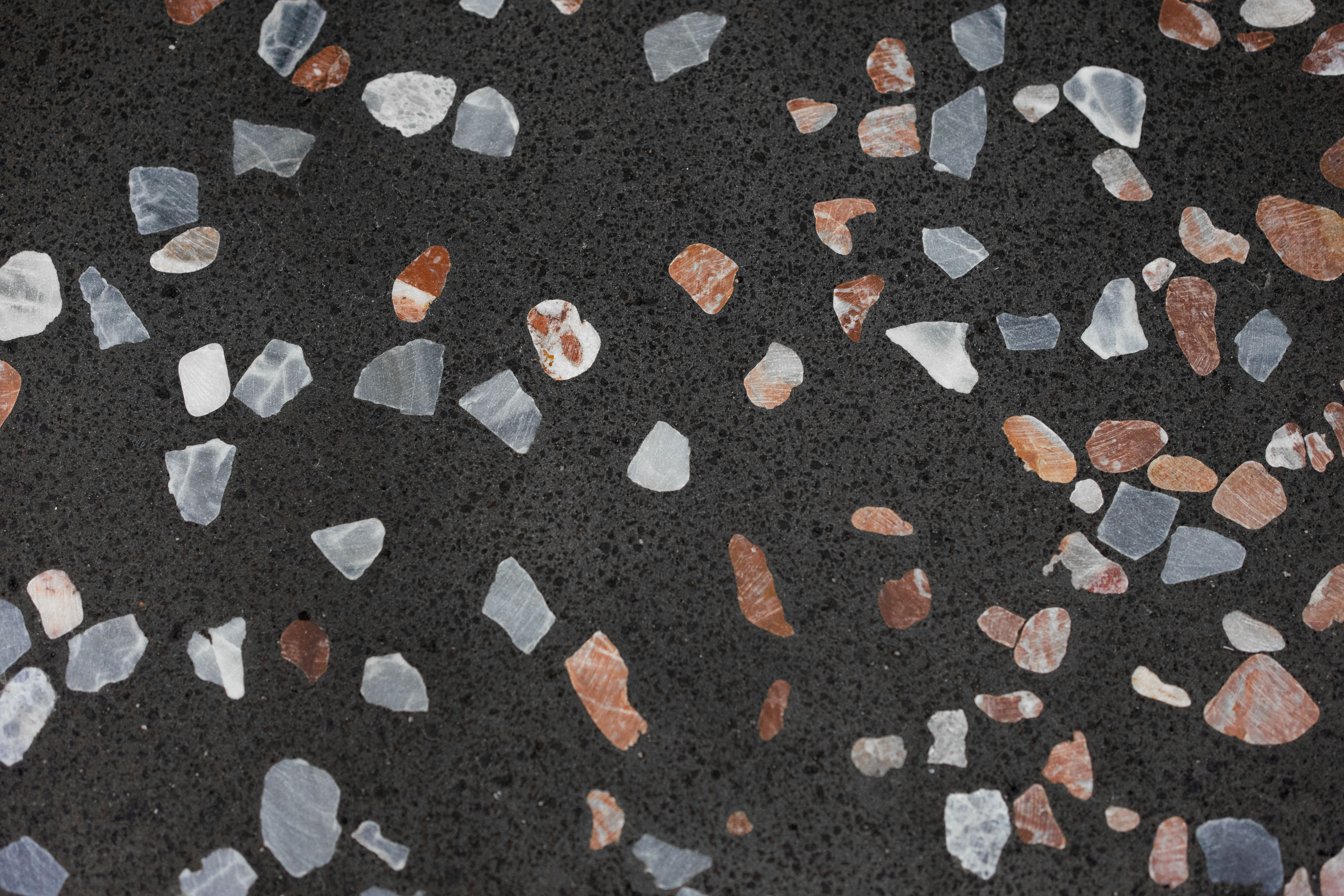

This ongoing project explores the transformative potential of slag as a low-CO2 cementitious binder, replacing traditional Portland cement. The high-temperature smelting process that slag undergoes during copper production creates unique material properties that allow it to be transformed into a binder for new building materials.

As our research progresses, we continue to uncover new aesthetic and practical possibilities, challenging traditional perceptions of sustainable materials. The resulting concrete combines structural integrity with distinctive surface qualities that reflect slag’s industrial origins.

At its core, this project aims to address two critical challenges: waste management and the carbon footprint of the built environment. By working closely with copper recycling facilities, research institutions, and architects, we are fostering a collaborative effort that extends beyond material development. Our goal is to establish a framework for industrial symbiosis—transforming today’s waste into tomorrow’s resource and redefining the possibilities for sustainable design and construction.

But what exactly is copper? The metal we know is only part of a much wider material story. Mining overburden, tailings, metal concentrates, rare metals like gold and silver, sulfuric acid, sulphate solution, slag, and more. Our primary focus in this investigation is slag, a byproduct of producing copper. Slag is the molten impurities cast aside during the smelting process into large mountainous heaps.

Slag is an inevitability of most metal production. The by-product is produced both during extraction directly from ore as well as recycling of scrap metal. Slag is also the reminder of an imperfect process, a residue left behind as a manmade stone. Remains of slag exist from ancient times speaking of long lost civilizations, and will remain far into the future to speak of our own.

This ongoing project explores the transformative potential of slag as a low-CO2 cementitious binder, replacing traditional Portland cement. The high-temperature smelting process that slag undergoes during copper production creates unique material properties that allow it to be transformed into a binder for new building materials.

As our research progresses, we continue to uncover new aesthetic and practical possibilities, challenging traditional perceptions of sustainable materials. The resulting concrete combines structural integrity with distinctive surface qualities that reflect slag’s industrial origins.

At its core, this project aims to address two critical challenges: waste management and the carbon footprint of the built environment. By working closely with copper recycling facilities, research institutions, and architects, we are fostering a collaborative effort that extends beyond material development. Our goal is to establish a framework for industrial symbiosis—transforming today’s waste into tomorrow’s resource and redefining the possibilities for sustainable design and construction.

Developed during our collaboration with the scientists at KU Leuven, and commissioned by Metallo Group, a local copper recycling factory, the first series reflects an exploration of interdisciplinary design methodology alongside an experimental making approach. We were introduced to the breadth of ongoing research, and in response designed and made a collection of pieces that showcases these scientific efforts and communicate alternative pathways towards a circular material culture.

The entire set of objects was exhibited at the copper factory, where members from the construction industry, metallurgy sectors, architects, scientists, and the factory workers were invited to view the waste in altogether new ways.

The entire set of objects was exhibited at the copper factory, where members from the construction industry, metallurgy sectors, architects, scientists, and the factory workers were invited to view the waste in altogether new ways.

Context

Copper is the oldest metal mined by humankind. Earliest traces of its mining appear alongside the first traces of aggriculture. As we learned to feed ourselves, so too did we learn to hunt for metals. Copper is one of the few metals that appears in pure form naturally, called ‘Native copper’.

The uses of copper have changed over the centuries. From a prized metal, to finding use in cooking, storage, medicine, boat-building, roofing, and finally, to electricity. Copper has always been prized, and has been quite effectively recycled across time; in fact, about 80% of all copper ever mined is still being circulated. Traditionally, copper was worked by a coppersmith by the power of hammer and fire, into volumous forms such as vessels. Today, that is all but lost. Instead, copper is extruded, spun, and coiled into the base elements that keep our world lit, keep us moving, and keep us connected.

Copper today spreads in sineway paths beneath our feet and through our walls, invisible to our everyday eye. And yet, it is crucial to the workings of our society, being key to mobility, communication, and electrification.

But the production of copper comes at a heavy cost, socially, economically, and environmentally. While it may have been common to find ore grades in the 20th century of nearly 40% copper purity, today mines are lucky if their ore has 0.2% copper grade. In fact, it is believed that ore quality continues to diminish, and we will soon run out of accessible copper. This decreasing ore quality means entire mountains are exumed to find traces of copper, requiring vast infrastructure and energy, disrupting local environments and peoples, and leaving ever-growing amounts of waste behind.

Slag is one such waste.

The uses of copper have changed over the centuries. From a prized metal, to finding use in cooking, storage, medicine, boat-building, roofing, and finally, to electricity. Copper has always been prized, and has been quite effectively recycled across time; in fact, about 80% of all copper ever mined is still being circulated. Traditionally, copper was worked by a coppersmith by the power of hammer and fire, into volumous forms such as vessels. Today, that is all but lost. Instead, copper is extruded, spun, and coiled into the base elements that keep our world lit, keep us moving, and keep us connected.

Copper today spreads in sineway paths beneath our feet and through our walls, invisible to our everyday eye. And yet, it is crucial to the workings of our society, being key to mobility, communication, and electrification.

But the production of copper comes at a heavy cost, socially, economically, and environmentally. While it may have been common to find ore grades in the 20th century of nearly 40% copper purity, today mines are lucky if their ore has 0.2% copper grade. In fact, it is believed that ore quality continues to diminish, and we will soon run out of accessible copper. This decreasing ore quality means entire mountains are exumed to find traces of copper, requiring vast infrastructure and energy, disrupting local environments and peoples, and leaving ever-growing amounts of waste behind.

Slag is one such waste.

Slag is the byproduct of the smelting process of copper. As the feedstock is melted, impurities are cast aside in a molten lava-like material. As it cools, a glassy black rock or sand is left behind. This is slag.

Slag is cast aside into mountainous heaps, standing in silhouettes against the sky. Today, these heaps continue to emerge and grow alongside their predecessors from the industrial era of the 19th century, a stark reminder of how methods of extraction, production and consumption have changed little across time.

Copper slag in particular has had little to no viable re-use strategies. This is primarily a result of contamination of slag and economics. Slags can be effectively cleaned from heavy metals, but costs to do so are high. Without a high-value demand, the lack of economic incentive to clean the slag curbs any attempts at reusing it.

However, as a result of public and legislative pressure, and a growing demand for alternative and secondary materials, some companies are investing in system to ensure their slag can be used in future settings. We work with some of these companies, and collaborate closely with scientists, in an effort to demonstrate to possibilities of using slag as an alternative building material. It is our hope that this drives more demand to fuel further interest from industry stakeholders.

Slag is cast aside into mountainous heaps, standing in silhouettes against the sky. Today, these heaps continue to emerge and grow alongside their predecessors from the industrial era of the 19th century, a stark reminder of how methods of extraction, production and consumption have changed little across time.

Copper slag in particular has had little to no viable re-use strategies. This is primarily a result of contamination of slag and economics. Slags can be effectively cleaned from heavy metals, but costs to do so are high. Without a high-value demand, the lack of economic incentive to clean the slag curbs any attempts at reusing it.

However, as a result of public and legislative pressure, and a growing demand for alternative and secondary materials, some companies are investing in system to ensure their slag can be used in future settings. We work with some of these companies, and collaborate closely with scientists, in an effort to demonstrate to possibilities of using slag as an alternative building material. It is our hope that this drives more demand to fuel further interest from industry stakeholders.